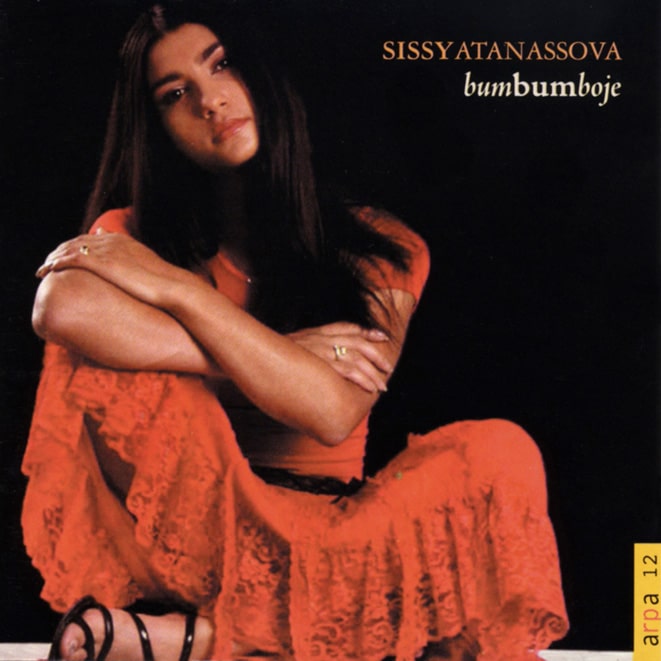

Cantante bulgara di origine zingara, Sissy Atanassova è a soli 24 anni la vera regina della “cialga”, (un genere musicale che impazza nei Balcani) e la sua voce, colonna sonora delle notti di Sofia è un invito alla trasgressione: genialità zingara, pulsioni “balc” e afrori mediorientali. Nata nel centro della Bulgaria, Sissy Atanassova comincia a cantare giovanissima a feste, matrimoni e battesimi, riscuotendo una crescente popolarità in tutta Europa, non ultime le improvvisazioni in lingua Rom nella colonna sonora del film di Giovanni Soldini “Brucio nel vento”. Recentemente ha inciso per la Sensible Records il suo primo disco italiano. Nel suo repertorio Sissy Atanassova alterna i motivi classici della comunità zingara con struggenti canzoni d’amore e canzoni tradizionali degli anni trenta delle tipiche osterie di Atene e Istambul che hanno caratterizzato la convivenza delle popolazioni balcaniche durante l’impero ottomano. A Romanengo sarà accompagnata da quattro musicisti e da due ballerine di Kiutchek, una sorta di danza del ventre.

La cialga è l’attuale folk-pop balcanico (pop-narodna) che mescola tratti zingareschi, ritmi sincopati delle musiche popolari, folk-pop turco ed elementi orientalistici e “arabeschi. Le orchestre di cialga sono quasi sempre formate da musicisti zingari perché capaci di reinterpretare le musiche tradizionali e farle proprie attraverso le contaminazioni. Gli strumenti di riferimento sono il clarinetto, la fisarmonica, la gadulka (strumento a corda tradizionale, simile al bouzuki greco) e la darabuka (strumento a percussione presente in tutta l’area balcanica e mediorientale). Nella cialga questi elementi della tradizione sono integrati con strumenti elettrici creando uno stile musicale nuovo ed eccitante, che comprende tradizione e modernità.

* * *

Most of the tracks selected for the debut record by the young Bulgarian singer of gipsy origin, Sissi Atanassova, are representative of a musical style, the Cialga – which is very popular these days in the Balkan area, and is also well known to create a lot of hype at ballrooms in all the main cities of that part of Europe. This genre can also be defined with terms like Folkpop or Ethnopop. Popular music from the Balkan area has always been contaminated by Eastern flavours coming from the domination of the Turkish Empire and from gipsy musical expressions. In recent years folkpop became more and more ethnic, very influenced by typical musical expression from gipsy minorities. From the early 80’s the Eastern stylistic element became part of Serbian folkpop: this style, called Pop-Narodna quickly arrived to Macedonia and Bulgaria through pirate recordings because of the strict monoethnic cultural policy of the Bulgarian government emphasizing “true” local music to the point that public performances of gipsy and Turkish music and a particular belly-dance called Kyuciek were banned.

The typical bands playing at Balkan and Bulgarian weddings, the so-called Svatbarski musicians, with a traditional repertoire made of several Eastern dances, risked to be arrested and prosecuted under charges of playing the banned Cialga gipsy music. This strict system of sanctions against music was an instrument of a systematic operation of ethnic segregation started in 1984 by the communist government of Todor Zhivkov that banned every custom or symbol belonging to the old Ottoman or Turkish culture and imposed to Turkish citizens to “bulgarize” their surnames. Such measures led to strikes and riots that were violently repressed and, at the end of 1989, to the forced mass migration to Turkey of about 250.000 Bulgarians of Turkish ethnicity.

Among them was the gipsy singer and accordion player Cigul (Binnaz, track 3) so nicknamed by the Turkish after the model of the car that he used to flee from Bulgaria (the “Zigul“”, or Fiat 124 made in Togliattigrad) and became in a few years a star of Cialga music in Turkey: he inspired several other singers and musicians like Ebru Gundes and Sinan Ozseker (Cinghenem, track 13), Ebru Yasar and Ufuk Sentire (Burak Yakimi, track 7).

The Cialga genre quickly spread into the Balkan capitals and is marked by contamination of gipsy tonalities with syncopated rhythms of the Balkan popular music and of oriental elements. These rhythms are partly derived from the Ottoman tradition and partly derived from a recent influence, especially in turkish folkpop, of arab tonalities, very popular with the audience. In Turkey Muslum Gurses (”the strong voice”) and Ibrahim Tatlises (”the sweet voice”) gigs are always long awaited and turn the ecstatic and joyful. The Cialga bands are typically formed by gipsy musicians. The instruments used are clarinet and gadulka (or saz or bouzouki, traditional string instrument) with the use of percussion (darabuka). These traditional lineups today are integrated with orchestras mainly formed by electronic instruments with a base accompaniment produced by a western drumkit, while hand percussion becomes a sort of rhythmic embellishment. This shift to a sort of “synth-pop” sound (Telefoni, track 4; Gelam Dade Tudureste, track 11) was inspired by the model of Yugoslavian pop-narodna (Vesa Kurkela). The abundant use of electronic instruments in Balkan folkpop is not only the product of modernization but also has economic reasons, due to both the prohibitive prices of traditional instruments and the possibility to reduce costs by using fewer musicians and with the help of synthesizers to reproduce the whole orchestra.

This new folkpop presents a lot of new oriental elements, not only in the melodic phrase but even in the sound of voices and instruments. Cialga clarinet players prefer nasal tones and hoarse tuning similar to the sound of zurla (ottoman oboe). Makam style (improvisation in Persian influenced ottoman classical music) goes along musical manners with added sounds and semitones, uncommon for western tonalities.

Listening to ethnopop or Balkan folkpop is not exactly related, if we think about contaminations, to a specific cultural identity. It is a new and exciting musical style, including a lot of music played in those territories for a very long time. The oriental accentuations have also a therapeutic effect, they became a means to protest that offsets the disappointed waits for the economic and political developments inspired to Europe, still hard to reach (Claire Levi). The western listener is involved in the exotic tonalities of Cialga and in its lively and sinuous rhythms, like being immersed in a foreign alterity but sounding familiar and reassuring.

The true involving force of this music is the production of unknown (for us) atmospheres, wrapping listeners with a sensation of sensual sharing culminating in the Kyuciek. Kyuciek is a sort of belly-dance performed in Cialga clubs by dancers dressed in next to nothing and with bright colours who with their movements inspire the audience to follow them into dances.This dance has a rhythmic structure in double metrics, with a binary system of voices called dum (low percussive bass) and tek (high). This musical and entertaining phenomenon is nevertheless opposed and criticized in Balkan countries by most of the local artistic and cultural avantgarde. It provokes the arrogance of the so-called cultural elite that defines this Balkan folkpop trend as a coarse and rough music and its lyrics, often vulgar and bare, ridiculous. Gipsy musicians are true performers of these musical trends, able to interpret in their way local traditional music and to appropriate through contaminations marking out the success of the current Balkan folkpop.

In this record Sissi Atanassova sings, inspired by her gipsy origins, some classic themes of gipsies from the South Balkans, played and sung during weddings and even for separations. From gipsy hymns, “Gelem, gelem” (track 8) and “Haidi Rumelay” (track 6), to yearning love songs “Chaje Shukarije (track 2) and “Zelenaja Aka” (track 5). In this view of Balkan song, remote and new, we can’t forget the style of traditional city songs that played a leading role in the typical Athens and Istanbul inns, with a trace of hazy nostalgia for that cultural and linguistic cosmopolitism typical of cohabitation of Balkan populations in some periods of Ottoman Empire (Aman Katerina Mu, track 10, sung both in Greek and in Turkish). Traditional Balkan popular lyrics are loaded with poetic qualities and harmony and reaches a unique romantic force. These features are typical particularly of Macedonian songs. Nevertheless we can discover similar melodies in the far island of Creta, like the traditional song sung by Sissi and dedicated to her mum (Mana, track 14).

Paolo Giulini