It’s no news, really, that jazz has spread throughout the world, especially to those of us who are hung up in this business for love or money or both. But sometimes it does come as a surprise that the players in other countries can be as good as they are and can sit there and play with the genuine U. S. article so well that just from listening you would never know they had not been born and brought up a block from Birdland.

That’s the way it is with this album and with its predecessor, “Jazz Is Universal.”

There was a time, of course, when a European soloist and a European band could be spotted instantly by any reasonably sharp-eared listener familiar with jazz. This is no longer true, as this album and others prove. In fact, it was not too long ago that a jazz record club conducted an interesting experiment. Without any label copy, an album done by a European band was sent out to a group of jazz critics all over the country. Nobody guessed the band and the guesses ranged all over the place, but always an American band.

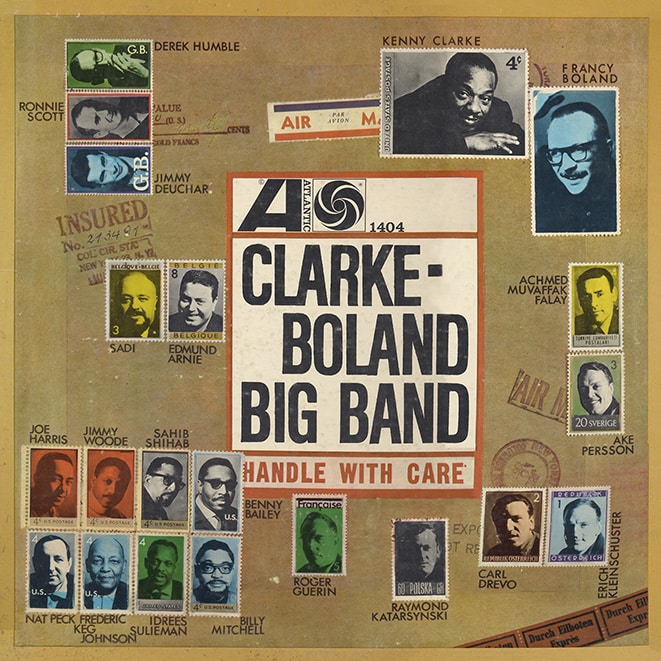

You could do the same with this one, though you’d be cheating a little since there are some first rate and first rank U.S. jazz musicians on the date. In fact, one of the things that makes this album (and the one before it) the first successful modern European big band album is the fact that the key chair is Kenny Clarke. Drums have been the weak spot in European groups ever since the advent of modern jazz. With the presence of Clarke, that question is eliminated with glorious finality. I have a suspicion that Kenny Clarke, placed in the rhythm section of almost any group, is the equal of half a dozen poll winners, several thousand volts and the pocket history of jazz.

He has solved, as John Lewis has pointed out, the problems of drums in the modern idiom. Given his presence, its hard NOT to swing. With him, pedestrian soloists are moved to play as never before, and good men become great.

The personnel of this band is interesting for a number of reasons. In the first place, it is ironic that a man such as trumpeter Idrees Sulieman has to go to Europe to be heard in such a benign context. It is also interesting to hear the two tenors, Ronnie Scotta (England) and Carl Drevo (Austria) smack up against Billy Mitche11 (USA). They don’t sound like they were born thousands of miles from the jazz milieu at all!

Another word in passing, on Billy Mitchell. As I have heard him more and more in the past couple of years, I have become convinced that he is one of the most under-rated jazz soloists around. I think he confirms this by his solos here. Sahib Shihab’s absence from the U.S. jazz scene is more keenly felt after hearing him on this album and the same can be said for Jimmy Woode (now permanently a European, after his marvellous time with Ellington).

Of the European soloists, I was particularly taken by the alto, Derek Humble, who has great swing and a warm, post-Bird style, and by the solidly modern playing of both Ronnie Scott and Ake Persson, the great Swedish trombonist. On Get Out Of My Town, Persson is convincingly at home with the ballad and his solo is memorable in many ways. He is also the leader of the section. Benny Bailey, another loss to the U.S. jazz scene, leads the trumpet section and the saxes follow young Mr. Humble. Francy Boland, who organized and produced this and the previous album, did the arrangements. Listen to the lovely, fat voicing of the saxophone ensemble Speedy Reeds, for an indication of how far the European arranging talent has progressed since the days of Ray Noble and the early R.A.F. band.

But finally, it all comes down to the drummer. There are three men who freed the rhythm section for modern jazz: Kenny Clarke, Max Roach and Art Blakey. Each is an individual, each has his place. I have always put them on a plateau far above their contemporaries (with the exception of Philly Joe) and comparisons are truly odious. Each of them could take such a band as this and lift it. And Clarke did on these sessions and never, once, does anything except serve. Not once does he insert his own presence in opposition to the soloists. This is the mark of the great musician and Kenny Clarke is undeniably such.

There are times when I can’t abide the sound of another small group and must hear a big band. If you are like this, you’ve got something to listen to here. If you are one of those who just simply never think of a big band, try this one and it may very well change your opinion of what can be done with greater numbers.

Listen to the trumpets go against each other on Get Out Of Town and Old Stuff. Dig the way the tenors sound on Speedy Reeds. Don’t miss Persson’s trombone solo on Get Out Of Town and the tenor-trumpet sequences in Sonor. In fact, dig in and listen to an album which has the life blood of jazz in it, the universal language of our time, the lingua Americana.

Ralph J. Gleason