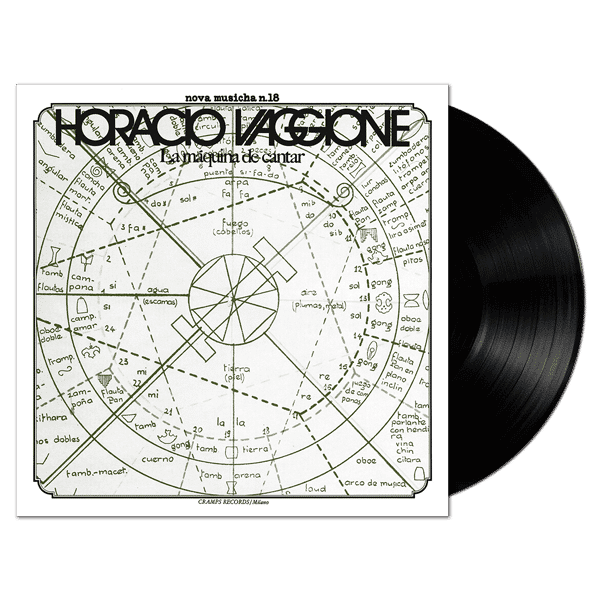

At long last, after remaining out of print for decades, the Milan based imprint, Dialogo, dives into the legendary catalog of Cramps, bringing forth the first ever vinyl reissue of Horacio Vaggione’s LP, “La Maquina de Cantar”, issued as the 18th instalment of the label’s Nova Musicha series in 1978 and among the most important examples of Latin American experimental music from the 1970s. Engrossing and creatively riveting, heard more than 40 years on its rippling electronic tones recast the terms of minimal music and shatter the historic perceptions of these sounds.

CRAMPS RECORDS REISSUES SERIES / NOVA MUSICHA N. 18

HORACIO VAGGIONE was born in Cordoba (Argentina) in 1943. He co-founded, in 1965, the Centro de Música Experimental de la Universidad de Cordoba, Argentina.

In 1966, he was awarded a Fullbright scholarship that allowed him to travel through the USA, where he visited several electronic music studios (Columbia, Illinois, California) and met John Cage. From 1969 to 1972, while living in Madrid, he belonged to a “live” electronic music group with Eduardo Polonio and Luis de Pablo. He was also in charge of the ALEA group’s electronic music studio.

In 1973, he visited the Far East. In 1974/75 he toured in the USA and Europe, more precisely with E. Wiener and the Kevan Cleary and Dance Company, while he was working in various electronic music studios (New York, Oakland, Montreal and Paris).

He currently lives in Paris, where he teaches electronic music techniques (synthesisers) and collaborates with Martin Davorin-Jagodic and Costin Miereanu on audio-visual performances. Triadas (68), Interface (68), Curriculum (69), Modelos del Universo (69), La Ascensión de Euclides (70), Kalimo (71), Last Continuum (75), Ending (75/76), Comment le temps passe (77), are his most recent works. (A catalogue of his pre-1968 works was published in Electronic Music Review 2/3, Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

His works have been presented at: Musica Viva, Frankfurt; Warsaw Autumn Festival; Electroacoustic Music Festival, Paris; Encuentros, Pamplona, Spain; Semanas de Nueva Música, Madrid; New York University; Mills College, California; Soho Performing Arts, New York; Maison de Radio France; Arc 2, Museum of Modern Art, Paris; University of Bordeaux; Entr-axes Festival, Brussels; etc.

La Maquina de Cantar was produced in 1971, using the IBM 7090 computer owned by the data processing centre of the University of Madrid. Sound synthesis was carried out by a team under the technical advice of Florentino Briones, director of the centre.

The complete system is a “hybrid”, as it is made up of digital and analogue operations. To begin, the composer writes his “score” in musical notation and then transcribes it into decimal numerical notation. This numerical notation is then transcribed into the machine’s language, in the form of punch cards; in this way, the computer receives all the data that it has to process and translate into sound. At the same time, the POPOVA program, which supports all the operations, is also launched. The sound is produced in the central unit of the IBM 7090, via high-speed magnetisation changes. So, the sound values will be expressed in the form of the number of magnetisation changes (bits). Once the sound and its envelope have been generated through this digital process, the next step is to send this information to an analogue section, consisting of a series of filters, a VCO (voltage-controlled oscillator), and an echo chamber.

Contrastingly, Ending is a work for live electronic keyboards. In this version, three Minimoog synthesisers (played by the composer) and a Yamaha organ (played by E. Wiener) were used. The work is dedicated to Robert Ashley.

Music is not a language: “What can be shown, cannot be said” (1)

Time is not neutral: “Changes do not create time; time literally creates changes” (2)

Time is not a line, movement is one thing, speech is another one.

For a proposition to make sense, I have to wait until the end: the last word will make me understand the whole. But my life makes sense right now. If I think I have to wait until the end for my life for it to make sense, it is because I am following a discourse (because I make my life a discourse…).

The tracks on this record are not a discourse. They become independently stable and generate their own continuity. They move, but they do not go anywhere.

Music and oblivion (3).

Tonal music was based on a functionalism of memory. Cage’s “pantonality” replaced it with a functionalism of oblivion. Now, nothing prevents this oblivion from being applied to tonality. The weirdness of what the musicians of the “new tonality” compose can no longer be judged according to the norms of memory, even if it is a “banal” C major. For such weirdness is exactly the fact that, for once, that C major changes our lives.

(…) Nothing, in this music, concerns memory; it is not at all static music, but rather incessantly renewed music, which is never heard twice in the same way.

(…) Flow-music, yet completely akin to the “oceanic” music of the oral tradition, be they non-European or, on the contrary, strictly Western: they all have in common that they build, in the multiplication of moments and in the profusion of events, a tradition exclusively grounded in oblivion, not in memory; a tradition that does not reproduce, literally (even when this task is entrusted to electro-acoustic tools), anything, any history, any institution.

(…) (But) the intensive moment is not even the fate of the full blossom of some individuals of probably extra-terrestrial origin, as the latest Stockhausen believes or pretends to believe.

(…) The oblivion that stirs and is activated in this very moment is no less temporal than time: it is, like nature according to Hölderlin, “more time than time”.

(…) Therefore oblivion, crossing different times, does not dominate or affect them, it only explicates its powerlessness on such matters, it lets them be without determining them. It is the very power of indetermination. More eschatological than eschatology, oblivion triggers every back-world, every theological background, to the advantage of this evident world. In this way, it opens up the still unheard-of non-cultural dimension of Revolution. “Un-remember like the unconscious”, this catchphrase by Jean-François Lyotard’s is a phrase of disorder, a phrase of oblivion. But music does not even need to refer to the unconscious in order to do so. It is enough for it to rely on Braque’s “perpetual sound of the source”. On the pure, primary flow of oblivion. Which is not even unconscious.

(Daniel Charles)

(1): Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

(2): Victor Zuckerland, Sound and Symbol.

(3): La Musique et l’oubli, fragments of Daniel Charles’ article published in Traverses/4, Paris 1976, reproduced with the author’s permission.