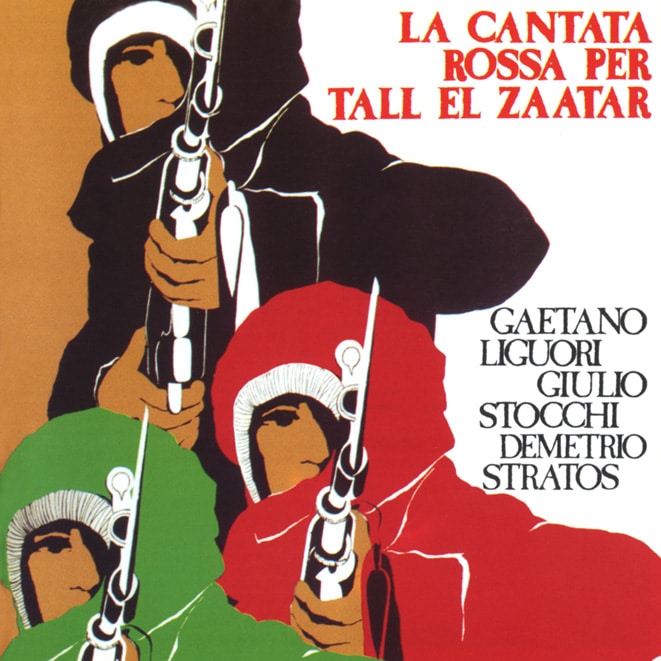

Demetrio Stratos from Area teamed up with jazz musicians Gaetano Liguori anf Giulio Stocchi for this special album released back in 1976, after the Tall El Zaatar massacre in Palestine.

“Liguori si serve della parola scritta che diventa oralità veemente, rabbiosa, gridata con tutto il potere dell’evocazione lirica… un’operazione anche per l’epoca molto coraggiosa”

(Guido Michelone, Alias, 27 gennaio 2001)

“Uno dei più importanti, impegnati e trasversali dischi del jazz tricolore” (P. Sca., il giorno, 7 giugno 2001)

“Perfetto amalgama di jazz e poesia, di cultura afroamericana e patrimonio folklorico, di avanguardia free e di world music ante literam”

(Guido Michelone, Jazz.it, maggio-luglio 2001)

“La cantata è sempre rossa” (Vivimilano, 6 giugno 2001)

“Un documento storico per lo sviluppo del jazz italiano”

(Claudio Sessa, coriere della sera, 7 giugno 2001)

“Una sorprendente libertà creativa… una commistione di linguaggi inebriante” (Flaviano De Luca, il manifesto, 23 giugno 2001)

“Si levò allora forte anche la voce di Demetrio Statos, che avrebbe taciuto per sempre da lì a non molto”

(Eddy Cilia, il mucchio, 17-23 luglio 2001)

“Un documento storico e politico quanto mai attuale”

(Giordano Casiraghi, tutto, settembre 2001)

“Musica carica di dolorosi sentimenti, di un grande bisogno di rinascita” (Vitorio Franchini, corriere della sera, 3 ottobre 2001)

Una fusione di jazz e letteratura, con l’emozione di ritrovare – assieme ai versi autorecitati da Stocchi – il canto di Demetrio Stratos” (Gian Mario Maletto, Il Sole-24 Ore, 24 febbraio 2002)

* * *

Black August In Arabic it’s “The hill of thyme”. It’s the year 1976, and Tall el Zaatar, it’s true yet much less poetic name, is a shantytown situated in East Beirut, which is the Christian part of the city. It’s a gigantic refugee camp that holds up to 30 thousand people: the main part Palestinians but also ex farmers from southern Lebanon, poor Armenians, Kurds, and a big part of factory workers in the numerous factories constructed in the area to take advantage of this reservoir of labor at a low cost. The Palestinian population, the poorest part of the camp, represents the tragic sedimentation of diverse incoming waves of refugees: the first arrives after ’48, kicked off of their own land, others in ’67, after the six day war, still others in ’70, after the “black September” in Jordan; the Lebanese, on the other hand, land in Tall el Zaatar searching for an escape from the Israeli bombardments in the south of Lebanon. The conditions of life are prohibitive: in 300 thousand square meters, the inhabitants are crammed in together until there are ten people in each available room. Along with the other shantytowns, like that of the Quarantine, near the port, Tall el Zaatar is part of Beirut’s “red belt”. Islands in the middle of the sea during a storm of the Lebanese civil war. Surrounding Tall el Zaatar is the hate of the small Christian bourgeoisie that lives in the surrounding neighborhoods, and the hostility in regards to a camp that doesn’t settle for being an intolerable Muslim Palestinian ghetto in Christian territory, but which has actually become a proud political- military fortress for the men of the Organization for the Liberation of Palestine of Arafat and for the liberal Lebanese of Jumblatt. Preceded by a violent campaign by the Phalange against the presence of Palestine in Lebanon, the war began in ’75: one of the episodes that detonated the conflict was the killing of twenty seven Lebanese and Palestinians that were assassinated while traveling from the camp at Sabra by bus – even this camp was destined to become sadly famous- to none other than that of Tall el Zaatar. In the course of the civil war the conservative troops decide to “homogenize” their sector of the capital and therefore to eliminate the diverse “non Christian” enclaves.

After having “re-cleansed” the small Palestinian camp at Dbayeh in Jounieh, by causing hundreds of deaths, at the beginning of ’76, the Phalanges pass to the neighborhood of the Quarantine: all the inhabitants that don’t make it in time to escape get passed over with firearms. The pressure of the Phalanges on Tall el Zaatar starts becoming heavy in January, with the first battles around the camp. After the massacre at the Quarantine the siege of Tall el Zaatar is extensively put into preventive measures. A few million Lebanese get out of there before it’s too late, the more political Palestinians and Lebanese stay put: they dig galleries, they strengthen the bunkers with reinforced concrete, they organize a small hospital with Chinese materials, they build iron rations, they acquire weapons and ammunition. The siege and the destruction of the Tall el Zaatar camp constitutes- comments today journalist Stefano Chiarini – “the epilogue of a downright process of ethnic cleansing ante litteram (ahead of its time), carried out by the conservative Christian Phalange troops from the eastern part of Beirut, controlled by them, in order to eliminate any type of Palestinian, Muslim, or liberal presence.” Syria intervenes in Lebanon by presenting itself as a peace maker in order to save from defeat the rightwing troops that are in difficulty up against the front offense of the OLP and from the leftwing Lebanese, who are in control of four fifths of Lebanon: the liberals are hostile towards the project of “Great Syria” which is one of Damascus’ aims and which on the contrary finds support among the rightwing Lebanese. The battle of Tall el Zaatar also corresponds to the intent to re-launch the civil war and Syria’s role as “peace maker”, who was forced to sign a “cease fire” with the Palestinians on January 21st.

The vise around Tall el Zaatar begins to tighten exactly the next day, the 22nd. The initiative is that of the rightwing troops of the national-liberal party. The Phalange follows them a few days later. The siege is made possible not only thanks to the go-ahead from Israel, sponsor of the rightwing formations ( the head of the ferocious guards of Credo, Abu Arz- Chiarini reminds us- lives today in northern Israel) but above all because of the support from Damascus.

Syrian and Israeli officials visit and observe the military operations against the OLP’s defense. From the 22nd to the 30th Tall el Zaatar is subjected to systematic bombardments. Millions of men are involved in the siege, with armed tanks, howitzers, missile launchers, ground missiles, and heavy machine- gunners. The ones trying to hold them back are about two thousand Palestinian and Lebanese fighters.

At the beginning of July an attempt by the Phalange to penetrate into the camp, is driven back with force. The besiegers then choose to take things the long way. Day after day the Phalanges artilleries butcher Tall el Zaatar. In order to re-supply themselves with water, the inhabitants have to go out into the open and reach one of the twenty points of distribution available: a thousand snipers positioned on the highest buildings of the surrounding neighborhoods keep the fountains under fire, causing hundreds of deaths. They are not few, the occupants of the camp that die of starvation, dehydration, tetanus, and gangrene. The Syrian cannons enter into action to prevent the liberal Palestinian posts that try to reach Tall el Zaatar from breaking the encircling. With no water, and no medicine, Tall el Zaatar resists, and with a radio as the only connection to the outside. The siege lasts fifty two days.

After more than seventy attacks on the defense, the by then exhausted inhabitants put an end to the resistance with the decision from the OLP: a part of the fighters is able to pass through the meshes of the enemy lines and bring itself into safety. In the course of the negotiations for the surrender, the Phalanges guarantee the safety of the civilians to the OLP and the Red Cross.

On the 12th of August the camp of Tall el Zaatar falls. For many of the survivors that come out like ghosts from the ruins of Tall el Zaatar, the illusion of salvation lasts very few seconds or hours: they are the victims of the butchery to which the besiegers abandon themselves, by betraying the sworn promises, and they are the victims of the Christian-Maronite inhabitants of the Quany neighborhood, where the survivors have to pass through to get away from Tall el Zaatar. The Christians have a frightening via crucis (purgatory) in store for them: between mass executions, torture, atrocities of all kinds, which don’t spare the children, women, or old, the number of deaths surpass two thousand in the one and only day of the surrender.

The cadavers get thrown onto trucks, brought up on the hill, unloaded amongst the ruins and recovered with concrete by bulldozers. The estimates are difficult. But out of around 20 thousand besiegers, at least half must have lost their lives in the course of the battle and the massacre that seals it. East Beirut has become an exclusively Christian sector controlled by the rightwing. The hill of thyme has become “the hill of shame”.

Marcello Lorrai, April 2001